The Talent Code: Unlocking the Secret of Skill in Sports, Art, Music, Math, and Just About Everything Else

Daniel Coyle

Description

A New York Times bestselling author explores cutting-edge brain science to learn where talent comes from, how it grows—and how we can make ourselves smarter.

How does a penniless Russian tennis club with one indoor court create more top 20 women players than the entire United States? How did a small town in rural Italy produce the dozens of painters and sculptors who ignited the Italian Renaissance? Why are so many great soccer players from Brazil?

Where does talent come from, and how does it grow?

New research has revealed that myelin, once considered an inert form of insulation for brain cells, may be the holy grail of acquiring skill. Journalist Daniel Coyle spent years investigating talent hotbeds, interviewing world-class practitioners (top soccer players, violinists, fighter, pilots, artists, and bank robbers) and neuroscientists. In clear, accessible language, he presents a solid strategy for skill acquisition—in athletics, fine arts, languages, science or math—that can be successfully applied through a person’s entire lifespan.

Key words: Skill Building, Talent, Winning

To read reviews of this book visit Goodreads

My Notes

Introduction

This book is about a simple idea: The talent hotbeds are doing the same thing. They have tapped into a neurological mechanism in which certain patters of targeted practice will build skill. Without realising it, they have entered a zone of accelerated learning that, while it can’t quite be bottled, can be accessed by those who know how.

“Skill is cellular insulation that wraps neural circuits and that grows in response to certain signals.”

The more time and energy you put into the right kind of practice – the longer you stay in the zone, firing the right signals through your circuits – the more skill you get.

Part 1: Deep Practice

Talent = the possession of repeatable skills that don’t depend on physical size.

Making progress became a matter of small failures, a rhythmic pattern of botches, as well as something else: a shared facial expression.

They were all purposely operating at the edges of their ability, so they will screw up.

The best way to understand the concept of deep practice is to do it. Take a few seconds to look at the following lists; spend the same amount of time on each one.

Now turn the page. Without looking, try to remember as many of the word pairs as you can. From which column do you recall more words?

If you’re like most people, it won’t even be close: you will remember more of the words in column B, the ones that contained fragments. Studies show you’ll remember three times as many. It’s as if, in those few seconds, your memory skills suddenly sharpened.

You stopped. You stumbled ever so briefly, then figured it out. You experienced a microsecond of struggle, and that microsecond made all the difference. You didn’t practice harder when you looked at column B. You practiced deeper.

Another example: let’s say you’re at a party and you’re struggling to remember someone’s name. If someone else gives you that name, the odds of you forgetting it again are high. But if you manage to retrieve the name on your own— to fire the signal yourself, as opposed to passively receiving the information—you’ll engrave it into your memory.

Deep practice is built on a paradox: struggling in certain targeted ways—operating at the edges of your ability, where you make mistakes—makes you smarter.

The more we generate impulses, encountering and overcoming difficulties, the more scaffolding we build. The more scaffolding we build, the faster we learn.

The trick is to choose a goal just beyond your present abilities; to target the struggle. Thrashing blindly doesn’t help. Reaching does.

This is why many successful ads involve some degree of cognitive work, such as the whiskey ad that featured the tag line “. . . ingle ells, . . . ingle ells . . . The holidays aren’t the same without J&B.”

Brazil’s secret weapon – Futsal. The ball was half the size but weighed twice as much; it hardly bounced at all. The pitch was also half the size. Consequently, signals fired more often, which built skills faster.

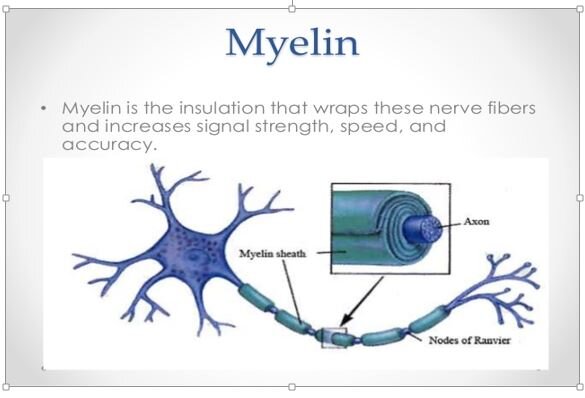

Myelin ‘is the key to talking, reading, learning skills, being human’. Copernican-size revolution: Fields, Bartzokis (doctors), and others claim that myelin, humble-looking insulation plays a key role in the way our brains function, particularly when it comes to acquiring skills

Revolution is built on three simple facts:

Every human movement, thought, or feeling is precisely timed electric signals travelling through a chain of neurons – a circuit of nerve fibres

Myelin is the insulation that wraps these nerve fibres and increases signal strength speed and accuracy

The more we fire a particular circuit, the more myelin optimises that circuit, and the stronger, faster, and more fluent our movements and thoughts become

What do good athletes do when they train? – They send precise impulses along wires that give the signal to myelinate the wire. They end up after the training with a super-duper wire – lots of bandwidth, a high-speed line. That’s what makes them different from the rest of us.

Skill is myelin insulation that wraps neural circuits and that grows according to certain signals. The story of skill and talent is the story of myelin.

Struggle is not optional – it’s neurologically required: in order to get your skill circuit to fire optimally, you must by definition fire the circuit sub optimally: you must make mistakes and pay attention to those mistakes; you must slowly teach your circuit. You must keep firing that circuit i.e. practicing – in order to keep myelin functioning properly. After all Myelin is living tissue.

Once a skill circuit is insulated, you can’t uninsulate it. That’s why habits are hard to break. The only way to change them is to build new habits by repeating new behaviours – by myelinating new circuits.

If you use your muscles in a certain way – by trying to lift things you can barely life – those muscles will respond by getting stronger. If you fire your skill circuits the right way – by trying hard to do things you can barely do, in deep practice – then your skill circuits will respond by getting faster and more fluent.

Every field is about 10,000 hours of repeated practice. This is called ‘deliberate practice’ and defined as a technique, seeking constant critical feedback, and focusing ruthlessly on shoring up weaknesses.

You need an obsessive desire to improve. A rage to master.

Art – So the renaissance believed – could be taught by a series of progressive steps

Grinding colours

Making copies

Work on the master’s design

To inventing one’s own paintings or sculptures

We are myelin beings. The broadband is the myelin, and the broadband installers are the green squid like oligodendrocytes, sensing the signals we send and insulating the corresponding circuits.

Skill consists of identifying important elements and grouping them into a meaningful framework. The name psychologists use for this is ‘chunking’.

What separates great performers is not an innate superpower but a slowly accrued act of construction and organisation: the building of the scaffolding, bolt by bolt and circuit by circuit – or as Mr. Myelin might say, wrap by wrap.

In 1985 Dr. Marian Diamond found that the left inferior parietal lobs of Einstein’s brain, though it had an average number of neurons, had significantly more glial cells, which produce and support myelin.

Chunking takes place in three dimensions;

Look at the task as a whole

Divide it into smaller chunks

Play with time, slowing the action down, then speeding it back up, to learn its inner architecture.

We are prewired to imitate (because we need to be accepted in the tribe, so we do what others do). So, to learn fast we can stare at or listen to the desired skill, then put yourself in the same situation as that person. This will have a big effect on your skill.

Slowing it down requires it looking like a ballet class – slow simple precise motions with emphasis on technique.

If you begin playing without technique, it’s a big mistake.

To build chunking back up;

Break a skill into its component pieces (circuits)

Memorise those pieces individually

Then link them together in progressively larger groupings (new, interconnected circuits).

Going slow allows you to attend more closely to errors, creating a higher degree of precision with each firing. It’s not how fast you can do it, it’s how slow you can do it correctly. Second, going slow helps the practice to develop something even more important: a working perception pf the skills internal blueprints – the shape and rhythm of the interlocking skill circuits.

To avoid the mistakes, first you have to feel them immediately.

What you’re really practicing is concentration. It’s a feeling.

Words that describe ‘deep practice’ are the sensation of their most productive practice (at the hotbeds): Attention, connect, build, whole, alert, focus, mistake, repeat, tiring, edge, awake.

Also, here is a list of words I didn’t here: natural, effortless, routine, automatic.

Deep practice is not simply about struggling: it’s about seeking out a particular struggle, which involves a cycle of distinct actions.

Pick a target

Reach for it

Evaluate the gap between the target and the reach

Return to Step One

One energising message on life: ‘better get busy’. Everything boils back down to training, doing it over and over.

Part 2: Ignition

Motivation is created and sustained by what I call ‘ignition’.

Ignition and deep practice work together to produce skill in exactly the same way that a gas tank combines with an engine to produce velocity in an automobile. Ignition supplies the energy, while deep practice translates that energy over time into forward progress.

Ignition is about the set of signals and subconscious forces that create our identity; the moments that lead us to say, ‘that is who I want to be.’

Long term commitment + high levels of practice = skills skyrocket.

What ignited the process wasn’t any innate skill or gene. It was a small, yet powerful idea: a vision of their ideal future selves, a vision that orientates, energised and accelerated progress, and that originated in the outside world.

Each signal is the motivational equivalent of a flashing red light: those people over there are doing something terrifically worthwhile. Each signal, is short, is about future belonging (vision). Seeing yourself on stage as one of them. Future belonging is a primal cue: a simple direct signal that activates our built-in motivational triggers, funnelling our energy and attention toward a goal.

“Pursuing a goal, having a motivation – all that predates consciousness” said John Bargh, a psychologist at Yale.

On adversity

Talking about losing a parent growing up.

You don’t have to be a psychologist to appreciate the massive outpouring of energy that can be created through adversity. For example: a child losing a parent.

This signal can alter a child’s relationship to the world, redefine his identity, and energise and orientate his mind to address the dangers and possibilities of life. Such adverse events nurture the development of a personality robust enough to overcome the many obstacles and frustrations standing in the path of achievement.

Talent requires deep practice

Deep practice requires vast amounts of energy

Primal ques trigger huge outpourings of energy

Primal ques

Tom flung primal ques at Ben with the precision of a circus knife thrower. In the space of a few sentences he managed to hit the bull’s eye of exclusivity (All I know is, it Suits Tom Sawyer…I reckon there ain’t one boy in a thousand) and scarcity (does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?...Aunt Polly’s awful particular about this fence). Primal ques make us want to do it. Primal cues have got to happen quickly, in a few sentences for it to hit our primitive emotive brain.

Praise & motivation

Half of the kids were praised for their intelligence (you must be smart at this) and the other half were praised for their effort (you must have worked really hard). The kids who were praised for effort got better grades than those praised for intelligence. Why? When children are praised for their intelligence “we tell them that that’s the name of the game: look smart, don’t risk making mistakes.”

Always praise the effort!!!

All of the places I visited praise was not constant but was given only when earned. Motivation often dips with increased levels of praise.

High motivation is not the kind of language that ‘ignites’ people. What works is precisely the opposite: not reaching up, but reaching down, speaking to the ground-level of effort, affirming the struggle. Phrases like ‘wow, you worked really hard’ or ‘good job’ motivate far better that what she calls empty praise.

Everything a student is doing should be connected to everything else around them. Every detail matters.

You will make mistakes. You will mess up. Everything is earned.

The primal cues the KIPP students received were the following;

You belong to a group

Your group is together in a strange and dangerous new world

That new world is shaped like a mountain, with college at the top (vision/goal).

Part 3: Master Coaching

The teachers and coaches I met in the hotbeds, were older and had been teaching for 30 or 40 years. They possessed the same sort of gaze: steady, deep, unblinking. They listened far more than they talked. They seemed allergic to giving pep talks or inspiring speeches; they spent most of their time offering small targeted, highly specific adjustments. They had an extraordinary sensitivity for the person they were teaching, customising each message to each student’s personality.

They had a skill at sensing the students’ needs and instantly producing the right signal to meet those needs.

He didn’t only tell them what to do; he became what they should do, communicating the goal with gesture, tone, rhythm and gaze. The signals were targeted, concise, unmissable and accurate.

Their personality, their core skill circuit – is to be like farmers: careful, deliberate cultivators of myelin.

A study was done on a basketball coach who had never lost a game, and won 10 national championships with his team; On the coach, they recorded 2,326 discrete acts of teaching;

6.9 per cent were compliments

6.6 per cent were expressions of displeasure

75 per cent was pure information. What do to, how to do it, when to intensify the activity.

One of the best forms of passing on this information was a three-part instruction that took no more than three seconds but is delivered with such clarity.

Model the right way to do something

Showed the incorrect way

And then remodel the right way

The basketball coach spent two hours each morning with assistants planning the days practice, then write out the minute by minute schedule on 3 x 5” cards. No detail was too small to be considered. He kept cards year on year so he could compare. He even showed players how to put on their socks at the start of the year, so they wouldn’t get blisters.

The best coaches ‘make decisions on the fly, at a pace equal to his players, in response to the details of his player’s actions’.

His skill was like a Gatling gun on the field. This, not that. Here, not there. His words and gestures were short sharp impulses to show the players the correct way. He was seeing and fixing errors. He was honing circuits. He was a virtuoso of deep practice.

His laws of learning are as follows;

Demonstration

Explanation

Imitation

Correction

Repetition

The importance of repetition until automaticity cannot be overstated. Repetition is the key to learning.

“Great teachers focus on what a student is saying and doing and are able to, by being so focused by their deep knowledge of the subject matter, to see and recognise the inarticulate stumbling, fumbling effort of the student who’s reaching toward mastery, and then connect to them with a targeted message.”

The key words in this sentence are ‘knowledge, recognise, connect’.

The coach’s skill is to locate the sweet spot on the edge of an individual’s ability, and to send the right signals to help the student to reach toward the right goal, over and over.

Coaches wanted to know about each student so they could customise their communication. They found out all about them and their personal life. They consistently monitored the student’s reaction to their coaching, checking whether their message was being absorbed. This led to a tell-tale rhythm of speech. The coach would deliver a chunk of information, then pause, hawk eyeing the listener to ensure received, then go again.

There is a skill to zap the student’s skill circuit;

Start with the goal / feeling the whole thing

Then the goal / feeling of certain sections

Then highly specific physical moved to hit the certain sections

Then motivate based on effort

Once hit the spot (even if still groping a little bit), add an extra later of difficulty… ‘now do it faster’ – push the buttons.

As a coach if A doesn’t work, try B or C. Change your input.

Truly great teachers connect with their students. There’s an empathy, a selflessness, because you’re not trying to tell the student something they know, but are finding, in their effort a place to make a real connection.

Good coaches help the right circuit to fire as much as possible.

You’ve got to make the student and independent thinker, a problem solver. They have got to figure things out for themselves.

A teacher is one who progressively makes himself unnecessary.

In 30 seconds, he explained the correct drop back motion in four distinct ways;

Ball on fire – tactile

Waiter – personification

Air plane – image

Butt to arm pit – physical